A Rockier Road to U.S. Citizenship? Findings of a Survey on Changing Naturalization Procedures

Randy Capps, Migration Policy Institute; Carlos Echeverría Estrada, Claremont Graduate University

Becoming a citizen benefits immigrants and U.S. communities in a variety of ways, including by promoting integration and enabling immigrants to vote and run for public office, sponsor close relatives for immigration, and travel visa free to many countries. Citizens also earn more than noncitizens with similar characteristics, and these higher earnings lead to greater economic activity and higher tax payments.

For the approximately 9 million immigrants eligible to naturalize, however, the hurdles to becoming a U.S. citizen appear to be growing. This report presents the Migration Policy Institute’s analysis of a 2019 national survey conducted by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center of 110 naturalization assistance providers. The study aims to understand how U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) naturalization procedures have changed during the Trump administration.

USCIS continues to approve the vast majority of citizenship applications, with an approval rate that has hovered around the 90-percent mark since fiscal year 2010, but the time it takes to process an application has grown considerably. This appears to be due at least in part to changing adjudication policies and practices, including those described by the surveyed organizations:

- About one-quarter of survey respondents reported their clients missed interviews when USCIS sent notices to incorrect addresses, sent them too late, or sent them to the attorney but not the applicant.

- Interviews had doubled in length, from 20–30 minutes to 45–60 minutes, according to one-quarter of respondents.

- More than one-third reported USCIS more often issued requests for evidence to support applications, especially for documents related to tax compliance and income, continuous residency and physical presence, marriage and child support, and criminal history.

- USCIS officers asked detailed questions not directly related to citizenship eligibility, and administered the English and civics tests differently, often more strictly, according to 10 percent of respondents.

These changes were underway before a trio of new 2020 developments that threaten to further increase the application backlog and make it more difficult for eligible immigrants to access citizenship: a COVID-19-related suspension of USCIS operations for three months, the likely furlough of two-thirds of the agency’s staff due to a major budget shortfall, and a planned increase in the cost of filing a citizenship application alongside new restrictions on eligibility for fee waivers for low-income applicants

You can access the full report at this link: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/changing-uscis-naturalization-procedures

How racial disparities in health affects political inequality

Javier M. Rodriguez, Ph.D., Arline T. Geronimus, Sc.D., John Bound, Ph.D., and Danny Dorling, Ph.D.

Equal opportunity to participate in politics is a basic requisite of democracy. Yet, in the U.S. the haves enjoy a participatory advantage over the have-nots—an advantage that is also reflected across racial lines. But an important source of participatory advantage comes from an usually overlooked suspect: Premature death. Black people, for example, die sooner than white people due to social—not genetic—factors. And because the dead cannot vote, premature mortality is a powerful force that dilutes the political voice of the poor and racial minorities like blacks and Native Americans.

Equal opportunity to participate in politics is a basic requisite of democracy. Yet, in the U.S. the haves enjoy a participatory advantage over the have-nots—an advantage that is also reflected across racial lines. But an important source of participatory advantage comes from an usually overlooked suspect: Premature death. Black people, for example, die sooner than white people due to social—not genetic—factors. And because the dead cannot vote, premature mortality is a powerful force that dilutes the political voice of the poor and racial minorities like blacks and Native Americans.

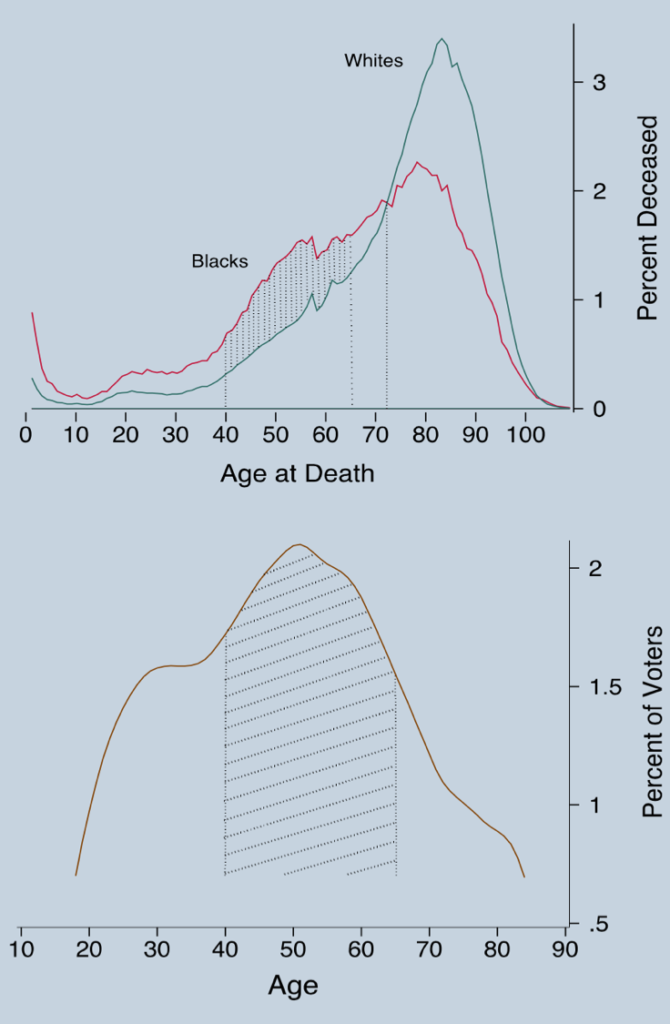

The figure at the top shows the age-at-death distribution of whites and blacks in 2004. It shows that blacks consistently die at higher rates than whites throughout their lifetime (the life expectancy of blacks in 2004 was 73 years). It also shows that the racial mortality gap is larger between the ages of 40 and 65—when socioeconomic differences amplify. The figure at the bottom is the age distribution of those who voted in the presidential election of 2004. And it shows that a critical portion of the electorate comes from people between the ages of 40 and 65. This means that black people are not only losing members of their community at a higher pace than whites but are also losing them during the age-range when political participation is most critical.

We calculated the total number of votes lost to excess mortality among black people between 1970 and 2004. Our results show that 2.7 million blacks should not have died between 1970 and 2004 if they had the mortality rate of their similar whites. Of these, 1.9 million would have survived to 2004, of which over 1.7 million would have been of voting age. Over 1 million black votes were not casted in the 2004 presidential election due to excess mortality. Even though these votes would not have been enough to change the presidential election outcome in 2004, we found that the votes lost to excess mortality among the black community would have changed the outcome of 7 senatorial and 11 gubernatorial elections between 1970 and 2004. This paper, coauthored by co-Director of the Inequality and Policy Research Center, Javier M. Rodríguez, was recently published in Social Science & Medicine.

Post-recession recovery arrives later to minority groups

Javier M. Rodríguez, PhD

Inequality and Policy Research Center

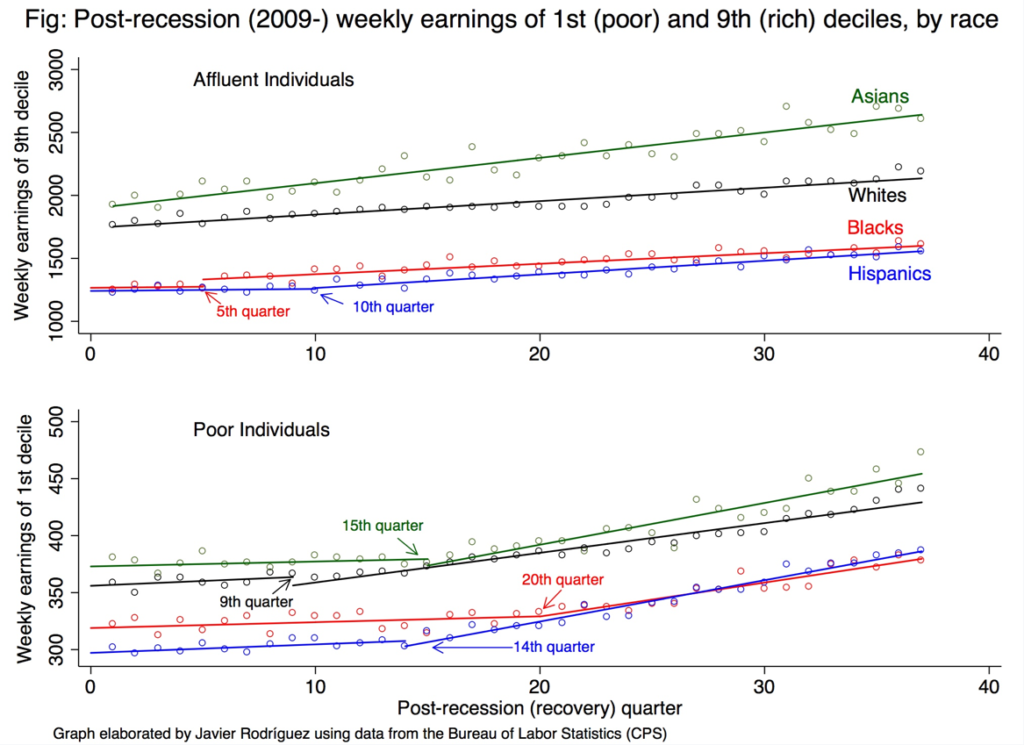

Researchers at the Inequality and Policy Research Center (IPRC) find that post-recession recovery arrives later for affluent Hispanics and black people, but much later for the poor (of any race), with poor black people having to wait a staggering 20 quarters (5 years) to see their incomes begin to increase.

This is especially worrisome considering the nature of business cycles, in which members of minority communities and the poor are also the first in experiencing unemployment and wage reduction. Less effective, productive time for wealth accumulation may contribute to perpetuate their disadvantage and, consequently, increasing income and wealth inequality between the races/ethnicities and socioeconomic statuses in the US.

The Impact of State Capacity on Inequality at the Subnational Level

Giacomo Di Pasquale & Alma Bezares Calderon, PhD

Inequality and Policy Research Center

Executive Summary

This report provides new evidence on how socioeconomic inequality is affected by the capacity of states to provide welfare services. Looking at 17 Latin American countries, we observe that there is strong variation in the presence of states across their territories, and that a state’s level of presence has consequences for the socioeconomic characteristics of the country. We also observe that in countries with high variation of subnational state capacity—that is, a state’s military, administrative, and institutional capabilities to effectively govern its territories and provide services to their citizens—social policies are not uniformly executed across territories. Accordingly, the effectiveness of such policies vary. And more so, depending on the level of territorial development where the policies are executed. Our analysis of the data shows that these dynamics have consequences for the levels of income inequality—which in turn exacerbate the differences in development between regions.

Background

This report focuses on Latin America, a region for a long time characterized by very high levels of income inequality. In Latin America, political and economic elites established—since Spanish and Portuguese colonialism in the 15th century—an inefficient structure of goods and services allocation that has prevented fair redistribution across subnational regions. Such inefficiency led to the configuration of weak states that are not able to effectively distribute public goods and services to the poor and invest little in the geographic areas with low state presence (but where the resources are most needed).

Whereas state penetration allows redistributing more in certain areas of the country, there are other areas isolated from the presence of the state where access to public goods and transfers are not possible. The absence of state presence impinges, in turn, the strengthen on governmental institutions, challenging to identify and take care of the needs of the population, extract resources, provide public goods and services, and redistribute resources appropriately. As the state presence is weaker in these areas, their population becomes less relevant in political terms (for example showing lower voter turnout and trust), further decreasing the interest of the government to deliver any type of public good or service to redistribute.

Analysis

We based our analysis on data obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Latin America Population Surveys from Vanderbilt University, and a series of surveys implemented by Luna and Soifer (2017)—which includes a set of questions that measure the territorial influence that the central state has across a country.

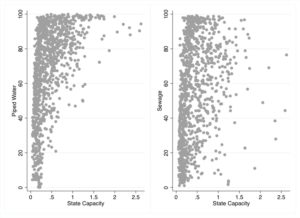

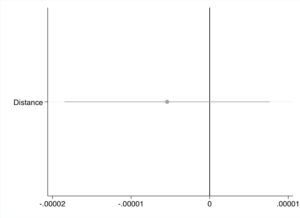

Our analysis shows a positive correlation between state capacity and income inequality, with a positive yet small coefficient on a model that regresses net income inequality on state capacity (proxied with the Myers score ), controlling for time and subnational factors (Figure 1). Results also show a positive relationship between territorial reach of the state and public goods provision (proxied with access to piped water and sewage system) (Figure 2). We also find a negative effect of a region’s distance to the capital on national income inequality (proxied with the Gini coefficient) (Figure 3). The results represented in the three figures suggest that higher levels of state capacity (in terms of provision of services and territorial reach) reduce inequality at the subnational level.

Conclusion

In this brief report the relationship between state capacity and inequality has been discussed. The conducted analysis on 17 Latin American countries shows that high levels of state capacity reduce inequality at the subnational level. When central states have the ability to provide welfare services, inequality across different regions of a country and different social classes tends to be lower. Furthermore, the analysis shows that the more local communities are far from the capital, the higher inequality tends to be in those communities, denoting difficulties (in this case in developing countries) for central states to fairly redistribute goods and services in all regions.

Vienne Wing-yan Lau, PhD candidate, CGU

The 2020 IPRC Best Policy Brief Award

Abstract

The present study demonstrates that self-interest may be utilized to motivate men to support gender inclusion initiatives in the workplace. In a 2 (Framing: Self-interest, Other-interest only) x 2 (Champion gender: Male, Female) factorial between-subject design with an Mechanical Turk sample, I find that framing a gender inclusion initiative as beneficial to self (as well as others) leads to more support from men, as compared to framing the initiative as beneficial to gender minority groups only. This effect is weaker among individuals with a higher score on social dominance orientation (SDO); however, having a male champion for gender inclusion initiatives helps attenuate it.

Introduction

Gender inequality persists in the workplace as women continue to be underrepresented in leadership and STEM (Fortune, 2019; Mundy, 2017) and face prejudice and discrimination in almost every aspect of their work-life (Frye, 2017; IWPP, 2018). To combat these challenges, many organizations and governments have been working to implement an array of initiatives and policies to promote women’s rights. Yet, this type of organizational intervention often yields mixed results (Kossek, Su, & Wu, 2017; Woetzel, 2015). The failure of these programs has been partly attributed to the inability to mobilize men to support this cause (Grant, 2014; Sherf, Tangirala, & Weber, 2017). The current framing of gender issues seems to widen the divide between men and women and is not likely to unite them to pursue the goal of gender equality together. To realize gender equality in the workplace, change efforts ought to encourage men to recognize their stake in the issue rather than highlighting their ‘contribution’ to the problem or excluding them altogether. In the present study, I use self-interest theory as a guiding framework to attempt to increase men’s support for gender inclusion initiatives in the workplace.

Data and Methods

Self-interest is related to costs and benefits regarding a particular subject (Bolino & Grant, 2015). One might have a high self-interest in a policy, for example, if they are immediately and personally affected by it (Liberman & Chaiken, 1996). Guiding by the purpose of this study, I derive three hypotheses.

First, I hypothesize that men would be more likely to support gender inclusion initiatives when framed as appealing to self-interest compared to when framed as appealing to other-interest only (Hypothesis 1). Social dominance orientation (SDO) refers to one’s preference for ingroup domination and superiority over outgroups (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Second, I hypothesize that SDO would moderate the relationship between framing and support for gender inclusion initiatives such that this relationship would be weaker among individuals with a high SDO (Hypothesis 2). Third, the moderating effect of SDO would be attenuated by champion gender, such that high SDO men would display more support for gender inclusion initiatives when the champion is male compared to when the champion is female (Hypothesis 3).

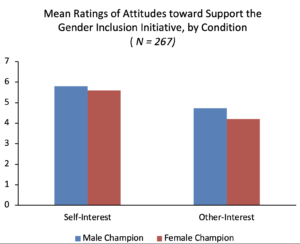

I employ a 2 (Framing: Self-interest, Other-interest only) x 2 (Champion gender: Male, Female) factorial between-subject experimental study to test the hypotheses set forth. I recruited 267 full-time, male employees from Mechanical Turk. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: Self-interest X male champion (n = 73), Self-interest X female champion (n = 67), Other-interest only X male champion (n = 67), and Other-interest only X female champion (n = 60). Participants were presented with a corporate communication video announcing the gender inclusion initiative. Those in the self-interest conditions learned that men would also benefit from the initiative but those in the other-interest only conditions were informed that men would not benefit from it. Those in the male champion conditions would see a male champion in the video and those in the female champion conditions would see a female champion in the video. After this, participants answered questions about manipulation check, support for the gender inclusion initiative, and SDO. Support for the gender inclusion was operationalized as attitudes toward the gender inclusion initiative, which were assessed with seven 7-point semantic differential items (Osgood, 1952; Siegel, Navarro, Tan, & Hyde, 2014). SDO was measured with the 8-item SDO7 Short Scale developed by Ho et al. (2015, α = .90).

Please note that with the absence of a control group in the current study, the findings are subject to threats to internal validity. Further research is needed to establish causal inference and directionality of the relationship.

Results and Discussion

The results show that self-interest is an effective way to garner men’s support for a gender inclusion initiative in organizations. Those who learn that the initiative would benefit both men and women were more likely to support the initiative compared to those who learned that it will only benefit others (see Figure 1); this was especially true among individuals with a low SDO. Having a male champion for the gender inclusion initiative, however, helps attenuate individuals with high SDO’s unfavorable attitudes toward the gender inclusion initiative.

Altogether, it should be clear to policymakers that an inclusive approach needs to be adopted in creating an inclusive workplace. Concurring with the discrimination-and-fairness perspective on diversity (Ely & Thomas, 2001), “policy and program approaches to involving men in achieving gender equality … must be framed within a human and women’s rights agenda and be intended to further women’s and men’s full access to and enjoyment of their human rights” (Peacock & Barker, 2014, p. 582). Leaders and policymakers should communicate their gender inclusion initiatives in a way that appeals to both men and women. Second, policymakers should identify powerful men who can serve as role models and allies for gender equality to inculcate a top-down change for their organizations. Third, it would be impactful if policymakers can identify potential male allies at different echelons and provide them with resources to instill bottom-up change. These can serve as the critical steps to cultivate a culture that supports the sustainability of a gender equality initiative (Cummings & Worley, 2014).

Conclusion

In this study, I test an inclusive approach to gender equality through reframing the issue to appeal to men’s self-interest. In doing so, organizations can garner more employee support for their gender inclusion initiatives. Furthermore, I demonstrate that when this idea is championed by a male leader, it is likely to elicit more support from men as well. By including both men and women, gender equality becomes more attainable.

Figure 1

Madisen Haines, DrPH program, School of Community and Global Health, CGU

The 2022 IPRC Best Policy Brief Award

Introduction

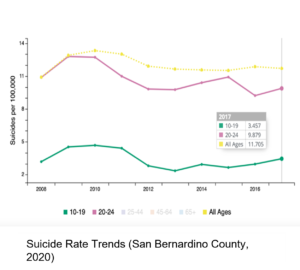

In the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents aged 10-24, demonstrating the need for effective prevention strategies. The causes of youth suicide are complex and multifaceted. Existing research shows that adolescents are susceptible to socio-economic factors and incur stressors from school closures, disrupted routines, social isolation, family economic hardships, and social hardships (Mayne et al., 2021). Other important causes of suicide among adolescents include academic expectation pressures, bullying (physical and online), physical, psychological and sexual abuse, substance abuse, and sexual identity (Edwards et al., 2021; Hochhauser et al., 2020; Joshi et al., 2019; Kreski et al., 2021; Schwartz et al. 2019; Wasserman et al., 2020; Whitmore et al, 2019; Yildiz et al, 2019).

Recent Trends

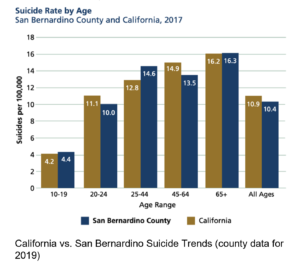

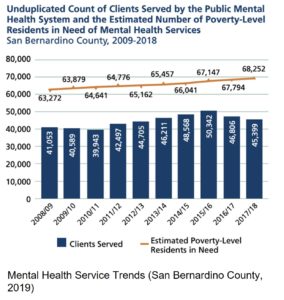

Suicide, suicide ideation, and attempts have been on the rise for adolescents in San Bernardino County. The data shows that youth suicide rate in the county reached 3.5 per 100,000 in 2017, while remaining slightly lower than the state average. The local government offers mental health services for population, but there are gaps in access and services associated with language, cultural, or gender identity barriers; the stigma of seeking help; and knowledge of the availability of services (Hochhauser et al., 2020; San Bernardino County, 2019). For instance, in 2017, the county provided mental health services to 45,400 people as compared to 68,300 of the estimated poverty-level residents in need of mental health services.

Role of K-12 schools in Youth Suicide Prevention

Learning activities and lesson plans raise awareness and understanding of social and physical support for suicide prevention. Currently, schools in San Bernardino County require annual teacher training on suicide awareness. Schools also conduct various children’s activities during the Mental Health Week as well as create posters and take-home information for parents to understand the warning signs. Existing strategies for suicide prevention applied in K-12 system could be further strengthened by integrating the following policy recommendations.

Policy Recommendations:

- Peer mentorship and leadership group activities to facilitate connectedness and coping mechanisms. Social support from peers prevents isolation and strengthens an individual’s social network to improve resilience against suicidal ideation (Kreski et. al., 2020; Singer et al., 2018).

- Social media and posters to reinforce help-seeking behavior (Elmquist, & McLaughlin, 2018; Hochhauser et al., 2020; Wasserman et al., 2020). It is important to know how to access support and resources.

- Annual surveys to assess suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and mental well-being of students for prevention and potential intervention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Mayne et al., 2021).